Living on 24 Hours a Day

Halfway through last year, I found myself overwhelmed by my schedule. There were simply too many things to do and not enough time. As we bookworms tend to do, I set out to find books that would teach me to wrangle my schedule.

I started with what felt like an obvious choice, Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity.

The central idea in Getting Things Done is that we can’t hold everything in our heads all the time. But we try to, so we constantly have many open “tabs”. We’re not only trying to keep track of what we’re currently doing but also all the things we need to do. The takeaway is to stop trying to keep everything in your head. Instead, write everything down and only focus on what you have to do at this moment.

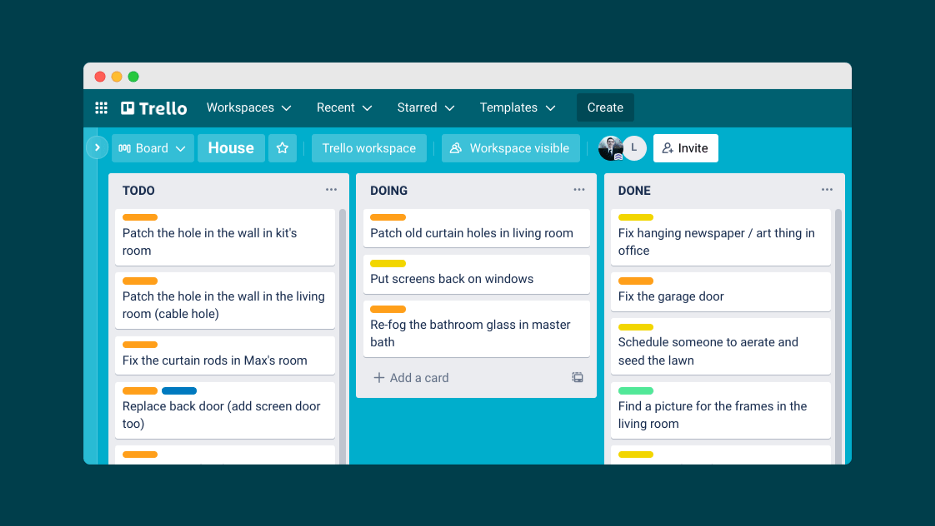

This led me to record every task and input. Now my TODO list lives on a few Trello boards instead of my head. When I switch contexts or decide what to do, I have a detailed and prioritized list of everything I need to do.

What did this get me? Increased productivity at work, a lot of progress on my budgeting project purchaseplan.io, and (incredibly) actually finishing house projects.

Yet, I still felt overwhelmed by all the things I wanted to do. Yes, I was using the time I had effectively, but I still didn’t have enough time. I still felt like 24 hours wasn’t enough.

How to Live on 24 Hours a Day

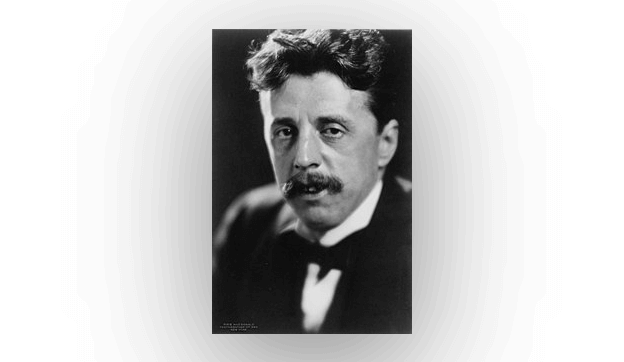

That’s when I stumbled across what would become my favorite book of 2021, How to Live on 24 Hours a Day by Arnold Bennet.

Have you heard of Arnold Bennet? I hadn’t.

One hundred and ten years ago, The New York Times Book Review claimed “Every one who wants to talk smartly about the books of the hour must read Arnold Bennet.”

He was a prolific writer, the most financially successful British author of his day. He published novels, edited a women’s journal, and even briefly ran England’s Ministry of Information during the First World War.

Unfortunately, shortly before his death, attacks by Virginia Woolf ruined his literary reputation, perhaps dooming him to literary omittance.

The Daily Routine

He wrote the book in the early 1900s while living in Paris, but he was thinking about the white-collar workers he knew back in London.

He gives, as an example, what he believes to be a typical Londoner of the day. This city-dwelling, white-collar worker very likely does not enjoy their job, potentially they outright hate it. So far, it seems like much hasn’t changed since 1908.

Our Londoner wakes up as late as possible, rushing out the door just in time to make the last train to the office. While on the train they peruse the newspaper. From 10 am until 6 pm they work with minimal effort. Shortly after six, they hop back on the train. As they head home they work up a tired feeling that will persist through the evening. Once home, they eat dinner, visit a friend, play a game, and eventually fall asleep.

Repeat the same thing every day.

During that time, it was popular to write articles about how to live on a certain income per day. Today, you’ll more likely see an article about how it’s impossible to live on minimum wage in America.

Bennet wonders, why aren’t there more articles on how to live on a certain allotment of hours per day?

He felt that there was something that we could change about our routines. Something that would allow us to not use our time more effectively, but more purposefully. He wasn’t thinking about productivity tips to cram more activity in. Instead, he was thinking about how to make the hours we have more fulfilling; about how to enrich and deepen the experience of life.

He starts with a question: are you ever using your full “horsepower”? Are you ever fully experiencing anything? Pushing yourself beyond what’s easy?

The answer very well could be no. If it’s not, if you consistently use all your energy and push yourself, what are you using that energy on? For some of us, it’s work. For others, it’s taking care of our kids. We give all our energy to that thing, working hard from nine to five (and potentially beyond!) with nothing left in our tank for the rest of the day.

So, we must begin by thinking of the day, not as nine to five, but as a full twenty-four hours separated into three chunks. There are roughly eight hours for sleep, eight hours for work, and eight hours remaining.

It’s those remaining eight hours that Bennet focuses on. How can you use them to their full potential? Those eight hours, for those who don’t love and live for work, are all we have to carve out a meaningful life.

I pause to consider what I and others use those eight hours for. Here’s a list, in no particular order: relaxing, exercising, socializing, consuming entertainment, shopping, eating, playing, perhaps even working some more (unfortunately).

In the worst case, those eight hours are frittered away. Not quite relaxing, not quite playing, not quite doing anything. We may pop Netflix on the TV and alternate between Twitter, Instagram, and the news, not quite focusing on anything. Maybe the reason feels valid. We’re too tired to really do anything but not sleepy, so it doesn’t make sense to go to bed. Besides, what else can you do on a weeknight without spending money?

Before anyone feels defensive, I’ll take a moment to fess up myself. I often find that after work I’ll be “too tired” to play with my kids, but I know my wife needs help. So I’ll find ways to be around the kids without fully interacting with them. I know that certain things elicit complaints, such as being on my computer; I avoid those, but I still find other ways to distract myself from reality. When I do this, I don’t really enjoy my time with my kids, I don’t really rest. I’m just wasting time.

So, what else can we do with our time?

Here’s where Bennet comes in with an idea.

Going Deeper

First, we need to evaluate how we’re using our eight “free” hours. As he evaluates his Londoner’s life, he notices the train commute in the morning where they read a newspaper. He asks for that time to be set aside for use later.

Next, he evaluates the evening. Let’s assume there are maybe five or six hours remaining in the day after work. Everyone will need some time to eat; truly, we need time to relax, because we are tired from work after all. He asks that his Londoner set aside just ninety minutes every other day, three days each week.

What does he end up with? Thirty minutes each morning before work and four and a half hours in the evenings.

Why? To live a deeper and more meaningful life.

He suggests that we use the evenings for learning. About what? It doesn’t matter, really. But you should spend your time learning about something. Ideally, something you care about. If you have a hobby or interest, learn about that. It could be music, movies, sports, or anything else. The point is that you spend your time learning about something you’re interested in so that you experience it more deeply.

Perhaps you don’t have hobbies, or you’re looking for something a little deeper. Here, he suggests learning about science, history, or philosophy. Spending a few hours each night reading Epictetus, Epicurus, and others can help you develop a framework for thinking about life in a deeper and more meaningful way.

And that’s exactly the point of the morning time he asks us to set aside. To think about life and reflect. Now, this isn’t meant to be idle thinking. Instead, it should be dedicated and focused reflection. It will require focus, which may be tough at first (it’s still tough for me).

When you put the two together, you have a regimen of learning and reflection designed to deepen the experiences you care about.

Words of caution

Bennet has a few words of caution for us.

First, he recommends that we start small. With a small amount of time and small expectations. Don’t try to apply this every day of the week. Give yourself a window of an hour for thirty minutes of reflection; expect interruptions and distractions.

Next, he recommends that we don’t become too strict about our regimen. The idea is for the learning and reflection to serve our life, not for our life to serve the regimen.

With anything that improves life, we have to avoid becoming a snob about it. There may be reasons that it doesn’t work for everyone, or why they can’t implement it. Improving ourselves is enough work already — there’s no need to worry about improving everyone else.

Finally, we should be cautious of failure at the beginning. Learning of a way to improve one's life can come with a strong motivation that disappears quickly when things get tough. Be careful not to overdo things.

Someone who Lived on 24 Hours a Day

The Engineering community at The New York Times (where I work) recently lost a long-time colleague and friend to COVID-19.

I, unfortunately, only knew him for a few months, even though he worked at The Times for fifteen years. But, during the outpouring of memories and shared grief over this loss, it became clear that he was someone who lived on 24 hours a day.

Colleagues shared memories of him writing limericks; painting, drawing, and creating for the office; sharing art and music; even, as he and his team walked back from lunch, taking quick excursions into historical churches to share what he knew about art and history.

I think he would have agreed with Arnold Bennet who said that nothing is mundane. It’s clear he spent a significant amount of time learning and reflecting on things that, to be honest, I, and perhaps others, have forgotten how to enjoy. The best part is that he chose to share his passion and knowledge of these things with all of us, making our lives and work better in the process.

All proceeds from Medium and Amazon Associate Links in the blog post will be donated to the GoFundMe for his family.

You can find How to Live on 24 Hours a Day on Amazon or you can read it for free here.